A Case for SOA in the Browser

So you are a web-developer. You write a lot of JavaScript. You have a large single-page application (SPA) with features to add and bugs to maintain. Over time the application grows in size and complexity. It becomes more difficult to modify one portion of the SPA without breaking another portion.

The company is growing and you are looking for ways to scale the team and code-base. You add unit tests. You add a linter. You add continuous integration. You modularize the code with ES2015 modules, webpack, and npm. Eventually you even introduce new, independent SPAs with each SPA being owned and deployed by independent squads. Congratulations, you have successfully introduced service-oriented architecture on the front-end, or have you?

What is Service-oriented Architecture?

The fundamental concept behind service-oriented architecture is a service. A service is an isolated piece of code which can only be interacted with through its API. Unlike a shared library, a service itself can be deployed independently of its consumers. Think of a back-end API. The API is the service and the browser is the consumer. The API is deployed independently of the front-end application. There is also only one deployed version of the API available at a URL.

Contrast a service to a shared library. A shared library is a piece of code that is bundled and deployed with your code. For example, libraries such as Express, Lodash, and React are all shared libraries included in your application’s distributable. Upgrading a version of a shared library requires a new deployment of that distributable.

Service-oriented architecture is an approach to building software where the application is composed of many independent and isolated services. Those services are independently deployable, generally non-versioned, and auto discoverable.

Why Service-oriented Architecture on the Front-end?

The benefits of SOA can be illustrated with this real life example from Canopy. At Canopy we have multiple single page applications. The first application is external to the customers and the second is internal, yet both applications share common functionality. That functionality includes among other things, authentication and error logging.

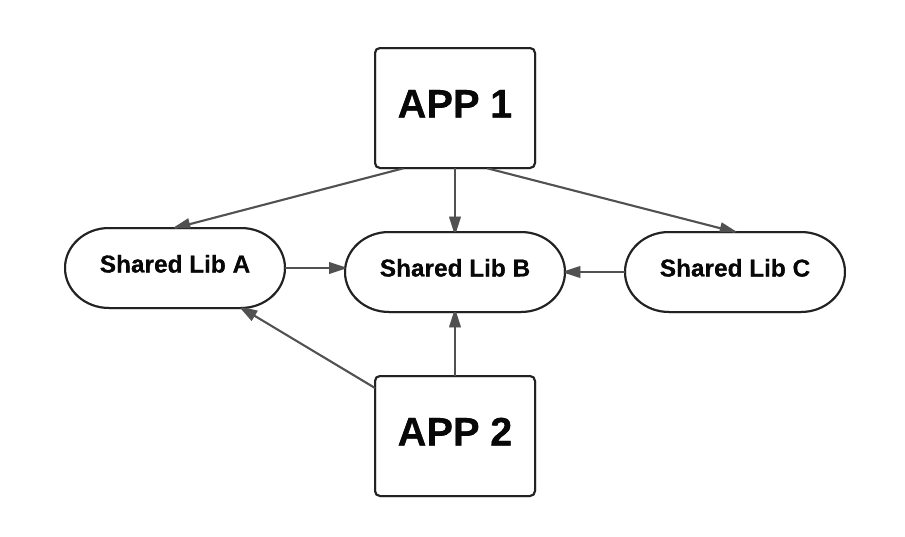

Shared libraries between two separate applications. App 1 depends upon shared libs a, b, and c. App 2 depends upon only shared libs a and b.

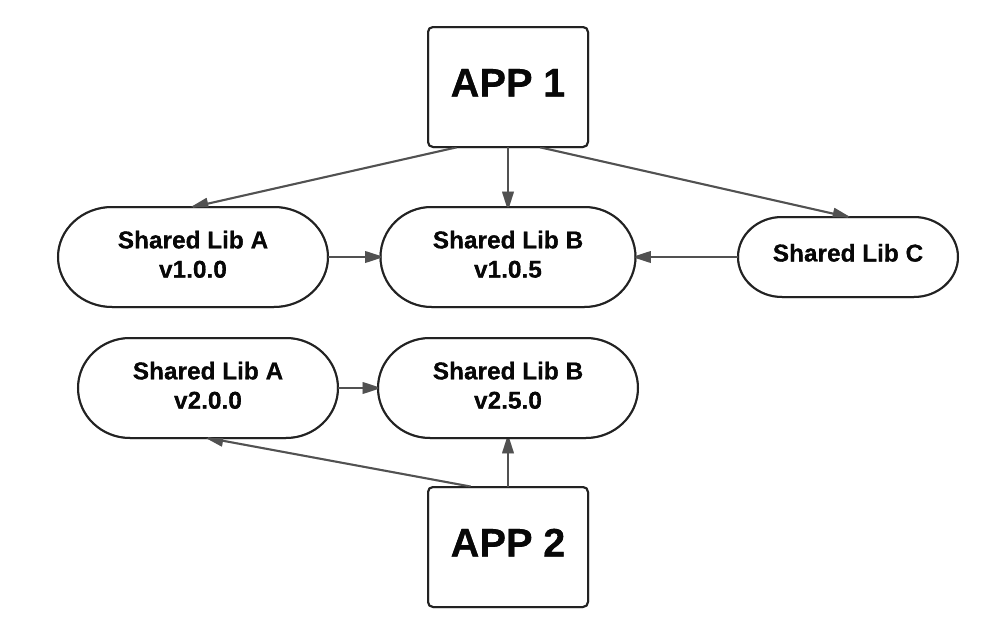

Overall the design looks good. The code is modularized and shared. The complexities arrive when we start to upgrade the code to different versions. For example, after a short period of time, App 2 (being internal only) is upgraded to a new beta version of the shared lib b. Because the shared a also depends upon b (and we don’t want multiple versions of b bundled) we also create a new version of a. This one change causes a rebuild and deploy of three separate pieces of code: App 2 and shared libs a and b. Our dependency structure is no longer quite so simple.

In reality, a duplicate instance of lib a and b exist in both apps. Each app does not point to the same instance of the shared libraries, even when they are the same version. This is more noticeable when the shared libraries have separate versions.

Now imagine a bug in both versions of shared lib b. In order to fix the problem, you will have to republish both versions of a and b as well as c. Also App 1 and App 2 will have to be re-deployed. That is five new versions to publish and two apps to redeploy, all to fix one bug. All downstream dependencies have to be redeployed when a single library is changed. This is deploy dependency hell.

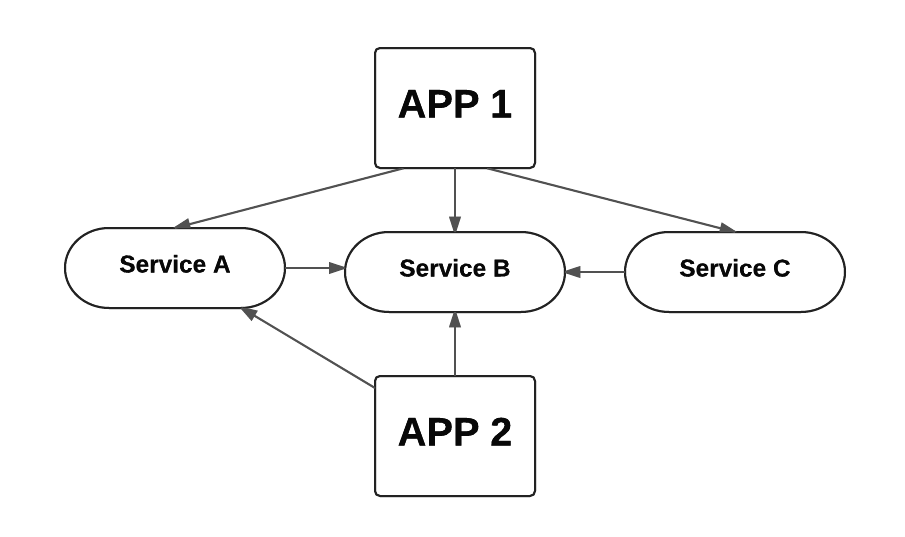

Service oriented architecture avoids these problems in a couple ways. Instead of bundling common dependencies, common code is shared through independent services. Services are not bundled, but rather loaded at run time. This also means that front-end services are not versioned (just like a back-end API). Both App 1 and App 2 load the exact same code for a front-end service.

Introducing sofe

Built upon the new ECMAScript module specification, sofe is a JavaScript library that enables independently deployable JavaScript services to be retrieved at run-time in the browser. Because the new module specification isn’t available within today’s browsers, sofe relies upon System.js to load services at run-time.

You can load a sofe service either with static or asynchronous imports.

// Static imports

import auth from "auth-service!sofe";

const user = auth.getLoggedInUser();

// Asynchronous imports

System.import("auth-service!sofe").then((auth) => auth.getLoggedInUser());

The real power behind sofe is that services are resolved at run-time, making them unversioned. If auth-service is redeployed, it is immediately made available to all upstream dependencies. The above scenario becomes much easier to resolve because there is only one version of each shared library as services. This is powerful because it allows you to deploy once, update everywhere. Also because the code is loaded at run-time, we can also enable developer tools to override what service is loaded into your application. Or in other words, you can test code on production without actually deploying to production.

The common dependencies are now services that are independent from the application code. Because services are unversioned, the dependency structure is again flat. Each service can individually be deployed and be available to every upstream dependency.

Obviously not all front-end code should be a service. Services have their own challenges. Specifically your code has to stay backwards compatible. But code can’t always be backwards compatible. Sometimes there needs to be breaking changes. The same problem exists for back-end services. A back-end API has to stay backwards compatible. Breaking changes on the back-end are generally solved by either creating an entirely new (versioned) API or implementing feature toggles within the API itself. The same solution applies to sofe services. An entirely new sofe service can be deployed or feature toggles can exist inside the front-end service. However it is solved, the key point is that services exist outside your application within their own distributable.

Another potential problem for sofe services is performance. Because they are loaded at run-time, performance can become a concern if you synchronously load too many services during bootstrap. Performance degradation can be mitigated by asynchronously loading larger services after the application bootstraps. Despite these challenges, there are many benefits to services on the front-end. The most exciting thing about sofe is there is now an option for services in the browser. You can decide what should and shouldn’t be a service.

Getting started with sofe requires only System.js. But to help you get started we have built sofe to work with a variety of technologies, including webpack, Babel, jspm, and the Chrome Developer Tools. Sofe is also actively used in production at Canopy Tax. We would love feedback on sofe and a number of open source projects that have been built around it. As you approach your next front-end project or look to improve your existing app, consider how it might benefit from service oriented architecture.

Read more about how to get started with sofe here.